[Note from Frolic: We are so excited to have K. Eason, author of How Rory Thorne Destroyed the Multiverse, guest posting about badass princess and more! Take it away!]

Confession, alert, flashing neon: for a long time, I refused to read romantic stories. And it’s all because of princesses.

Let me back up. See, romance to child-self-me was what happened to the princess at the end of the fairy tale. Happily ever after meant kissing a boy the princess didn’t even know. And then marrying him. And everyone acted like that was a good thing.

And then there were the princesses themselves. Bah. I wanted no part of it. My objection was mostly utilitarian: I did not like dresses, and I hated fancy shoes. Such things got in the way of my real life goals, which involved pretending to be a dinosaur. The whole business just seemed…restrictive. I mean, princesses–and here I was drawing on the popular culture and fairy tale versions, which were the only ones I had at that point–always started from some bad place: a tower, a position of servitude, a place of abuse or unfairness. They never escaped on their own; ultimately, their liberation rested on some prince coming to save them. Whom they then had to kiss. And marry. While wearing pointy shoes.

The word used was often romantic, but to me, it seemed like the princess was some kind of reward for male bravery (and usually male violence, though I didn’t notice that until much later).

I could not have articulated that, of course, in childhood. I just recoiled from happily ever after defined by fancy dresses and impractical shoes (glass slippers? what?) and kissing some strange guy. Best not to be a princess at all, I thought. Best to be a dinosaur. Or…guiltily, I thought this, because I knew I shouldn’t say it too loudly…to be Maleficent, and be able to turn into a dragon.

And then I saw Star Wars, and Leia, and I had to reconsider princess as a category. Now there were princesses who smarted off to their companions and did things and didn’t have to wear stupid dresses until the very end when everyone was dressed up and miserable. Also, people listened to what they said. And they were clever. I mean, sure, Luke and Han and Chewie came and rescued Leia at first, but only because she was smart enough to send R2D2 out with a message. And she was tough: Darth-freaking-Vader used the Force and more conventional means of interrogation (okay, torture) and she never gave up the secret base. The other princesses, well. See above. Stupid footwear. Married to strangers.

In college, I found medieval literature–Mallory, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Chaucer—and learned a new (old) definition for romance: a narrative in which there is a quest or adventure of some kind–spiritual or physical–which requires bravery and good character to resolve; a love interest is not central, and might not even be there at all. There was room for a princess in a romance, if she were also the action-hero.

I began to look for those stories, about girls and women who were the dragon, the hero, whatever. When I couldn’t find them, I made them up. I got into table-top role-playing and created my own old-school romantic heroines: kick-ass, brave, love-interests optional (but pretty frequent). It was relatively easy to substitute out the male heroes for female, to put a woman in the active role. For a long time I reveled in the freedom of a woman or a girl who could do things, who could choose, and whose choices, romantic or otherwise, didn’t necessitate a loss of freedom.

A key feature of the medieval romance is that the knight must prove his courtesie–his worthiness, if you will–before he uses his martial prowess to complete the quest. I was intrigued by a denial of the possibility of force, an acknowledgement something other than violence, right before violence was used to solve the problem. I didn’t, and don’t, mind violence–it’s a key feature of my favorite genre(s)–but I found myself wondering, well, is it a necessary feature, or just a customary one?

I kept circling back to the princesses of my childhood. What about them, trapped in their towers, both real and metaphorical, with their wicked stepmothers and cruel step-sisters? Was there a way to be a good princess in a bad situation? And, I don’t know, self-rescue? Could I write a medieval romance with a princess-lead where the quest is achieved without violence?

Which was how I came to write How Rory Thorne Destroyed the Multiverse. The story is the love-child of a fairy tale and a medieval romance with the princess as the hero. Rory, like so many princesses, has little choice about being someone’s stranger-bride. Her prince isn’t even charming. But then she discovers a brewing political coup, and realizes that her prince is in trouble. He needs help, and she’s it. Allied with the second son of the would-be usurper, armed only with her wits and her courtesie, Rory embarks on her quest. If she succeeds, she might just not rescue herself (and her prince) and the kingdom. She might also destroy the multiverse.

About the Author:

K. Eason is a lecturer at the University of California, Irvine, where she and her composition students tackle important topics such as the zombie apocalypse, the humanity of cyborgs, and whether or not Beowulf is a good guy. Her previous publications include the On the Bones of Gods fantasy series with 47North, and she has had short fiction published in Cabinet-des-Fées, Jabberwocky 4, Crossed Genres, and Kaleidotrope.

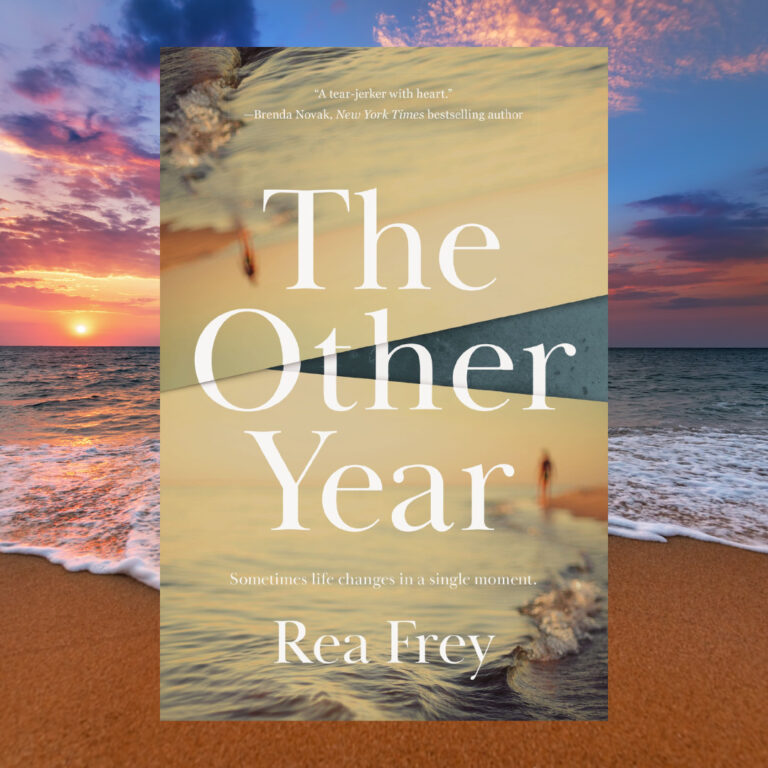

How Rory Thorne Destroyed the Multiverse by K. Eason, out now!

First in a duology that reimagines fairy tale tropes within a space opera—The Princess Bride meets Princess Leia.

Rory Thorne is a princess with thirteen fairy blessings, the most important of which is to see through flattery and platitudes. As the eldest daughter, she always imagined she’d inherit her father’s throne and govern the interplanetary Thorne Consortium.

Then her father is assassinated, her mother gives birth to a son, and Rory is betrothed to the prince of a distant world.

When Rory arrives in her new home, she uncovers a treacherous plot to unseat her newly betrothed and usurp his throne. An unscrupulous minister has conspired to name himself Regent to the minor (and somewhat foolish) prince. With only her wits and a small team of allies, Rory must outmaneuver the Regent and rescue the prince.

How Rory Thorne Destroyed the Multiverse is a feminist reimagining of familiar fairytale tropes and a story of resistance and self-determination—how small acts of rebellion can lead a princess to not just save herself, but change the course of history.