Down and Dirty

Chamber pots, head lice, the pox—and I don’t mean the kind prefaced by “chicken”—writing historical romance calls for striking a balance between authenticity and contemporary sensibilities. I still recall, with lingering discomfort, watching Braveheart for the first time. Spending nearly three hours with Mel Gibson’s William Wallace and his men blanketed in sweat, blood, and woad was nearly as excruciating for me as the final execution scene.

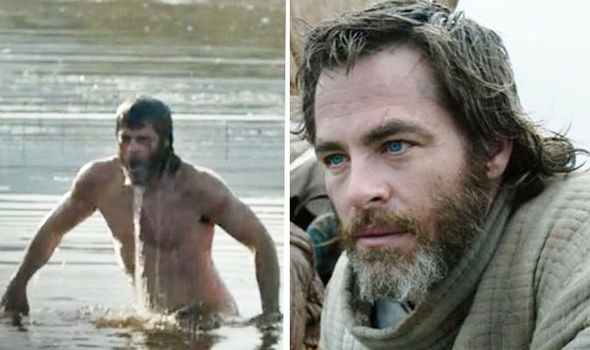

In Netflix’s Outlaw King, a recent edition to the pantheon of ruddy bloody muddy Scottish-set medieval war sagas, Chris Pine’s Robert the Bruce doesn’t fare much better with the soap and suds. He does, however, wade nude out of a freezing pond. (Think Collin Firth’s Mr. Darcy but with… shrinkage). The birthday suit booty comes an hour and 27 minutes into the movie. There’s a lot of earnest speechifying and grizzly guts and garters killing to be got through first.

Pro tip: Pour yourself a nice mug of mead and fast forward.

Just how dirty were our forbearers? Certainly, people from earlier eras couldn’t have kept up the level of cleanliness available today when, for most of us, access to hot water is as easy as turning on the tap. But was abject filth really everyone’s reality? Certainly, those with wealth and lands and minions at their beck and call could be clean if they chose. You don’t have to delve too deeply into the historical record to find that many were.

Getting Wet

In Medieval times, providing a bath was part and parcel of the hospitality on offer to visiting knights and other honored male guests. The ritual was performed in private and hands-on by the chatelaine of the castle—talk about your potentially sexy romance novel scenario!

England’s Queen Elizabeth I couldn’t abide malodors from her courtiers or herself. Her commitment to cleanliness called for hauling her private bath on every stop of every Royal Progress.

But what about everyone else, those whose social station fell somewhere between lordly and lowly?

Making an indoor bath happen was a time-consuming labor. Water was brought in from an outside well, heated in the kitchen, and then carried in heavy, copper-lined buckets up flights of often steep, winding stairs. But there were alternatives. The remains of hot rocks baths, communal bathing pools lined with smooth stone and sometimes roofed against inclement weather, have been excavated throughout Scotland and parts of Ireland. Some sites were proximate to naturally occurring thermal springs, but others were not. In the latter case, buckets of heated stones or rocks were periodically added to the water, maintaining a semi-constant warmish temperature. Quelle steamy story setup for a historical romance writer!

Regency rake and male fashionista, Beau Brummell is known as much for bringing fastidiousness into vogue as he is for his elaborate snowy waterfall neck cloth and champagne-based boot blacking. We have Brummell to thank for bringing regular bathing to the in crowd.

Toothsome Tales

Medieval people also took regular care of their teeth, and I don’t only mean visiting the blacksmith or other local tooth puller once things got… ugly. Tooth powders were the precursors to Crest and Colgate. Certain wood barks were ideal for cleaning between teeth. Chewing fennel and other breath-freshening seeds was a common practice between and after meals—early Altoids! Recipes for soaps and bath salts were passed down from mother to daughter.

Getting Physical

By the late 1990’s and early aughts, historical romances began embracing grittier, less airbrushed depictions of hygiene and intimacy. Take, for example, Outlander by Diana Gabaldon, the launch to her brilliant and beloved Scottish time travel series. During Jamie and Claire’s wedding night lovemaking, his curious kisses stray… south. The usually randy Claire halts him, protesting that he must be put off by her unwashed state. Smiling, Jamie likens the situation to a horse learning his mare’s scent. And proceeds to prove how very not put off he is.

We don’t call them “heroes” for nothing.

By now most of us are familiar with the infamous tampon scene in Fifty Shades of Grey by E.L. James. But in historical romances, our heroines rarely have their periods until they don’t and then only in the service of the story, notably advancing the tried-and-true “marriage of convenience” trope. Rarely do we see in fiction what dealing with menstruation must have meant for our foremothers. Plug-like devices for blocking flow are traceable to ancient Egypt (papyrus) and Rome (wool). However, the modern, mass-produced tampon wasn’t invented until 1929 by Dr. Earle Haas. Patented in 1931, Haas later trademarked his remarkably liberating new product as “Tampax.”

Such advances are all well and good but what about having the personal space to put them into practice? Not even gentlewoman Jane Austen had a room of her own. In Irish Eyes, my historical women’s fiction novel, my Irish immigrant heroine shares a three-room Lower East Side, New York tenement flat with a family of seven. Finding the privacy to change clothes, bathe, relieve herself and manage menstruation as she must is a challenge few of us can imagine facing. And yet as documented in How The Other Half Lives by reformer turn-of-the-century reformer, Jacob Riis those were the very circumstances in which the vast majority of immigrant arrivals to New York found themselves.

Romance readers are an exceptionally savvy lot. Anachronisms invariably jar us from the story; too many may well have us pulling the plug without reaching the end. And yet none of us truly knows what it was to live in a previous century or, for that matter, generation. Our research is done in the service of the story. Fortunately, historical romance focuses not on the ordinary but on the extraordinary, not on tepid tenderness but on grand passion and great stakes, not on how dark, dreary and dirty life can be but on how amazing real love is and always will be.